As much as you might like to believe that you are a rational being whose decisions are founded purely on facts and logic, the truth is that most people are influenced by all sorts of inconsequential variables when they make decisions. Consider this well-known study, which found that judges are dramatically more likely to be lenient in their sentencing after lunch; though their job is to make impartial decisions based on the facts before them, most judges can’t help but succumb to unrecognized biases.

Fortunately, by knowing about potential biases you might have, you can limit their effect on your ability to make sound decisions. Here are a few common types of biases plaguing many people and why they shouldn’t impact your decision-making process.

Survivorship Bias

Likely, you love reading about the most profitable companies and what makes them tick, about startups that made it big, about small businesses that are thriving and why. Yet, you probably almost never seek out stories of when businesses crash and burn.

The survivorship bias is a bias of seeing only success, to the point of ignoring failure. This can provide you with a sense of unwarranted optimism, that you will certainly achieve victory. However, recognizing the possibility of failure and planning for it is an important element of making good decisions.

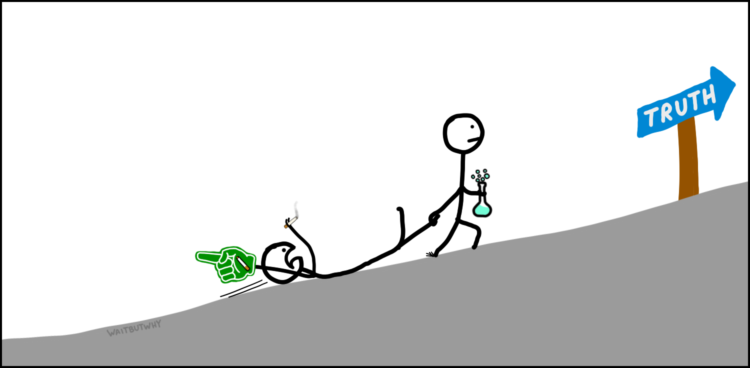

Confirmation Bias

When you believe something, you have an instinct to look for proof to back up your belief. Unfortunately, this means you likely ignore evidence that contradicts your belief, and it might lead you to outright reject data that doesn’t align with your expectations.

This is the confirmation bias — that you will naturally search for confirmation of your existing views — and it is a difficult bias to break. Taking a decision-making biases online course could provide you with a step-by-step system that helps you avoid succumbing to the confirmation bias.

IKEA Effect

When you buy a desk from IKEA, you are responsible for putting the pieces together in the right order and the right way. Because you have been part of the project of building your desk, you are more likely to highly value this desk over any others that have already come assembled.

The IKEA effect, named for the DIY nature of their furniture, is a bias for projects that you have personally been part of. Because you have contributed to something, you likely feel that it is more valuable or beneficial than other projects you didn’t participate in. When making decisions, it is important to remove your influence from the equation.

Anchoring Bias

In first grade, you learned that George Washington chopped down a cherry tree. Now, no matter how many historians tell you that story is a myth, you won’t forget the trivia about our nation’s first president, and you might continue to believe that a portion of that tale is true.

Also called “first impression bias,” the anchoring bias is the tendency to make decisions based on the first information you learn, regardless of whether that information is accurate or beneficial. Smart negotiators can use anchoring bias to their advantage by making the first offer, which helps frame the negotiations around that offer. To thwart anchoring bias, you can slow down and carefully consider your decision and the evidence you are using to support it.

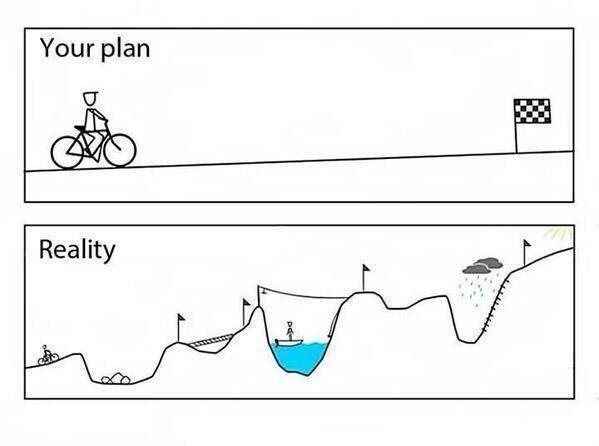

Planning Fallacy

When you are planning your day, you allot an appropriate amount of time to complete each task: 30 minutes to commute to work, 15 minutes to answer emails, one hour for the morning meeting, etc. In this way, you can pack as much productivity into your day as possible. Yet, in practice, none of these tasks will take exactly this amount of time, and you will likely finish your day with some tasks incomplete or utterly undone.

The planning fallacy is a bias that presumes a best-case situation, that elements of a plan will work as expected. However, delays always occur. You should practice saying “no” to certain projects that could derail your decision, and you should always budget extra time into your plan just in case.

You are only human, so your decisions are bound to suffer from some flaw regardless of how diligent you are in identifying and eliminating your biases. By studying strategic decision-making processes and slowing down your decision making, you should be able to make better, less biased decisions in life and in your career.